The First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system has two major functions: to create a stable government by turning a minority of votes into a parliamentary majority, and to represent the division of political views among voters. This year's general election got it half right: Labour won control of government with a large majority while opposition parties were denied 200 MPs they would have gained if seats had been distributed strictly in proportion to votes.

The electoral system spectacularly manufactured a government majority from a minority of votes. The new Labour government won 63.3 percent of the seats in the House of Commons. Starmer's majority was similar to Tony Blair's first two majorities and greater than any Conservative majority since 1935. However, Labour's popular vote, 33.7 percent, was the lowest of any governing party in British electoral history. This vote share is only 1.6% higher than what Labour got under Jeremy Corbyn in 2019.

The Labour government won its massive parliament majority because the majority of constituency votes were divided among five parties in England and six in Scotland and Wales. In the extreme case of South West Norfolk, Labour took the seat from Liz Truss with only 26.1 percent of the vote.

Thanks to the FPTP system, the Labour government is now the leading party in Parliament with 412 MPs instead of the 219 MPs it would have been awarded if seats had been distributed strictly in proportion to the party's share of the popular vote. Even though Labour is vulnerable to losing seats in a mid-term slump, in by-elections, and from defections and expulsions, it is securely in control of British government for the next five years.

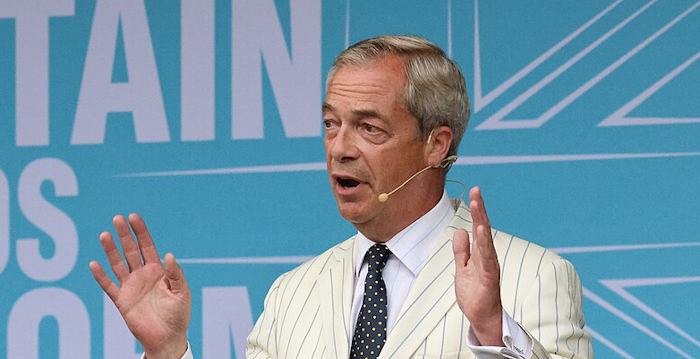

Calls for Reform: Nigel Farage has joined the Liberal Democrats and Greens in advocating for scrapping the First Past the Post system after Reform won just 5 seats from 14.9% of votes cast in the General Election.

The FPTP system's creation of a majority government has come about by misrepresenting the views of voters and penalizing some parties far more than others. Although the Reform Party finished third with 14.3 percent of the popular vote, it won only five MPs, less than one percent of the 650 seats in the House of Commons. The Greens also suffered from the electoral system. They took 6.7 percent of the popular vote, which would have won 43 MPs in a proportional representation system rather than the four they were awarded by the FPTP system. By contrast, the Liberal Democrats, with 12.2 percent of the popular vote, won almost the same proportion of seats, gaining 72 MPs.

The Conservative Party's share of the vote fell by almost half, 19.1 percentage points, its lowest in history, losing two-thirds of its seats. However, the Tories still managed to hold on to 121 MPs instead of experiencing an almost total wipeout. Instead of swinging to the Official Opposition, as happens in a two-party system, the Conservative vote split four ways. More than a quarter went to the right-wing Reform Party; another chunk switched tactically to the centrist Liberal Democrats; some former supporters stayed home; and a limited fraction of disaffected Tories voted Labour. Thus, the gap between the Tory share of votes and seats was only five percentage points. However, the fragmentation of supporters means that the new Tory leader will be pulled in opposing directions to regain support.

While party leaders like to claim they represent all the people, neither Rishi Sunak, Keir Starmer nor Nigel Farage secured as much as half the vote in winning their own constituency. Both Sunak and Starmer appear to have lost upwards of a fifth or more of their previous constituency vote. In Sunak's case, the loss was the fault of his government's record while Starmer lost more than 10,000 votes to a left-wing pro-Palestine candidate, Andrew Feinstein, and the Green Party. Ed Davey was the only major party leader to gain just over half their constituency's vote.

While the facts are clear, decisions about electoral reform do not depend on facts but on political power. With a secure Commons' majority, Labour can quash any move to make the electoral system more proportional. Likewise, as the runner-up party, the Conservatives' priority is to get sufficiently ahead of Labour in votes to be leveraged back into government as before. The Liberal Democrats' success from tactical campaigning in the FPTP system has not ended its commitment to a proportional representation system that could produce a hung parliament and give more seats to the Reform Party of Nigel Farage than to the Liberal Democrats.

Prof Richard Rose is Britain's senior election expert, having written about 18 elections since 1959.