Keir Starmer entered Downing Street with a 290-seat lead over the Conservatives even though the Labour Party won the lowest share in history of the popular vote for the governing party. Labour more than doubled the number of its MPs from the 202 it won in 2019 even though its share of the popular rose by only 1.5 percent, because the Conservative Party vote fell so much that it lost two-thirds of its MPs.

The big winners from the 20 percent drop in the Conservative vote were other Opposition parties, especially Reform and the Liberal Democrats. However, differences in support at the constituency level meant that the first-past-the-post electoral system enabled the Liberal Democrats to take 66 seats from the Conservatives compared to Reform gaining two Tory seats.

The Reform Party of Nigel Farage came third with 14 percent of the popular vote but finished tied for sixth in MPs with Ulster's Democratic Union Party because their vote was evenly spread. The party lost only 32 deposits because its constituency vote fell below five percent. Its major impact was to win over one-quarter of voters who had cast a Tory ballot in 2019. There are now 144 seats where the combined Conservative-Reform vote is greater than that of the Labour MP and 26 seats won by Liberal Democrats where this is the case.

The Liberal Democrats enjoyed more than a sixfold increase in their MPs to 73 even though their share of the popular vote rose by less than one percent. This was the result of the party concentrating its campaigning in fewer than one hundred seats. Thus, Liberal Democrat candidates lost their deposit in 229 constituencies. Less than half their vote came from those who had voted Liberal Democrat at the previous election. Most of their gains came from tactical anti-Tory voting in seats where the party was second to the Conservatives; in 65 of the seats it won the Tories are now the second-place party.

The Green Party more than doubled their share of the British vote to 6.7 percent and won four MPs. The party showed evidence of establishing a nationwide appeal by reducing the number of lost deposits from 466 to 258, and by coming second in the vote of 18 to 24 year olds with 18 percent of their vote. It finished second in forty seats.

Scotland shows how a five-party system distorts results. The SNP vote fell by one-third and it lost more than five-sixths of its seats. Yet it is second in total votes and only five percentage points behind Labour and second place in every seat it didn't win. In Wales Labour's vote fell 4 percent while Reform won 17 percent. However, Labour was the big gainer in seats, taking nine more than at the previous election.

While Rishi Sunak's strategy of winning back support from those who had voted Conservative in 2019 made sense in theory, it failed in practice. It not only lost 25 percent of its former voters to Reform but also 17 percent to Liberal Democrats or Labour, and five percent to other parties.

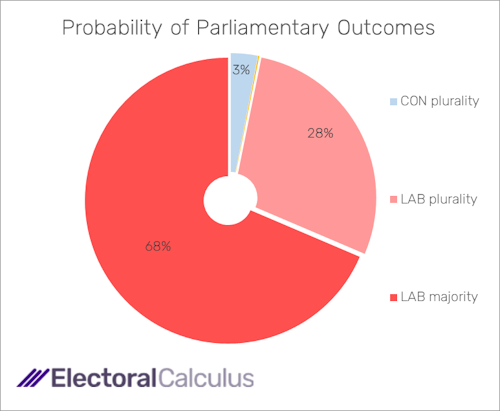

It is early days to speculate on what a 2029 election will produce but three important known unknowns are immanent in the July result. When Labour hits its mid-term slump, which opposition parties will benefit in the opinion polls and in by-elections? Come the 2029 general election will Nigel Farage's Reform Party still be nominating candidates in seats which the Tories need to win to regain competitiveness? Will opposition parties win enough seats collectively to deprive Labour of its majority but leave it a minority government because they are politically too divided from each other to form a coalition government?

Prof Richard Rose has writing about 18 British general elections since 1959 and regards the July result as in a class of its own.