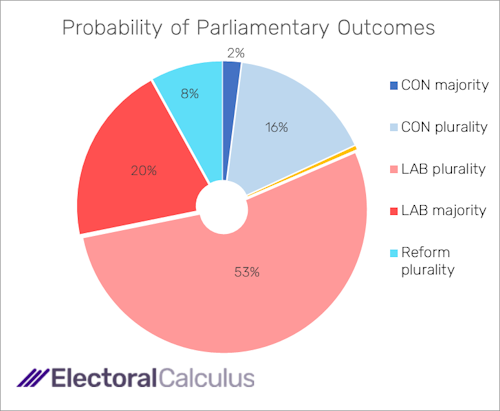

Labour won a massive parliamentary majority with barely a third of the popular vote, but pushing bad news at voters in its first six months of office has pushed its luck too far. Its fall in opinion polls to barely one-quarter of the vote would cost Labour its majority in the House of Commons if a general election were held today.

The loss of a parliamentary majority does not mean that Labour is automatically ejected from office. Poll support for the official opposition, the Conservatives, has only gone up one-tenth of one percent since the general election. It is nonetheless able to gain 55 seats due to Labour's support falling. This leaves the Tories 134 seats behind Labour and even further behind the absolute majority needed to take firm control of Downing Street.

The Reform Party of Nigel Farage has been the biggest gainer in votes, up 7.2 percentage points since the general election. It remains penalized by the first-past-the post electoral system because its support is widespread. With more than one-fifth of the vote, Reform would have less than six percent of seats in a new parliament. All but two of its additional 31 MPs of its gains would be from Labour.

A spreadsheet calculation shows that Labour's slump would give opposition parties a collective majority of 339 MPs. However, assembling a majority to produce a vote of No Confidence in a Labour minority government is easier said than done, when opposition MPs are fragmented among 12 different parties plus 11 independents.

The addition of a projected 71 Liberal Democrats and 36 Reform MPs would produce 283 votes with No Confidence in a minority Labour government with 310 MPs. Adding 24 Scottish and Welsh nationalist MPs to a No Confidence vote would bring the opposition up to 307 MPs, but still fall short of surpassing Labour by four MPs. After that, calculations get very problematic.

Northern Ireland's 18 MPs could split three ways. Sinn Fein would be sure to abstain, Unionists inclined to vote against Labour and others to abstain or support Labour. Green Party MPs might prefer to give half a cheer for Labour's climate change policies by abstaining rather than cast votes that could lead to Conservative government with less commitment to climate change.

The joker in any forecast in the next House of Commons is who the independents are as well as how many. At present, the 11 independents are a mixture of Muslim MPs who defeated a Labour candidate by running on a pro-Gaza platform in a heavily Muslim constituency; MPs elected as Labour but losing the party whip for taking left-wing positions; a moderate Labour MP who resigned from the party; and Jeremy Corbyn.

This forecast throws a shadow on the current political situation. Even though it offers the prospect of Labour holding on to office after the next election, one hundred or more Labour MPs would lose their seats. The promise of added Conservative strength is offset by the evidence that Tory MPs would remain on the opposition benches for another five years.

Neither Sir Keir Starmer or Kemi Badenoch need speculate about the outcome of a vote of confidence in the government in the current current Commons. The major threat each faces is a vote of no confidence in their leadership by their own backbench MPs.

Prof Richard Rose, director of the Centre for the Study of Public Policy, Strathclyde University, is Britain's senior election expert. He has been writing about elections at home and abroad since 1960.